Profoto made a big splash recently when they released the A1 – dubbed the world’s smallest studio flash.

I was fortunate enough to get a hands-on training day with the A1 at Ashridge House in leafy Hertfordshire, where I got to play with the new flash alongside existing Profoto gear. Our tutor for the day was Holly Wren, a self-confessed Profoto fan and user of the brand. I caught up with Holly after the official launch to ask her views on the A1 and how she found working with it during the training sessions.

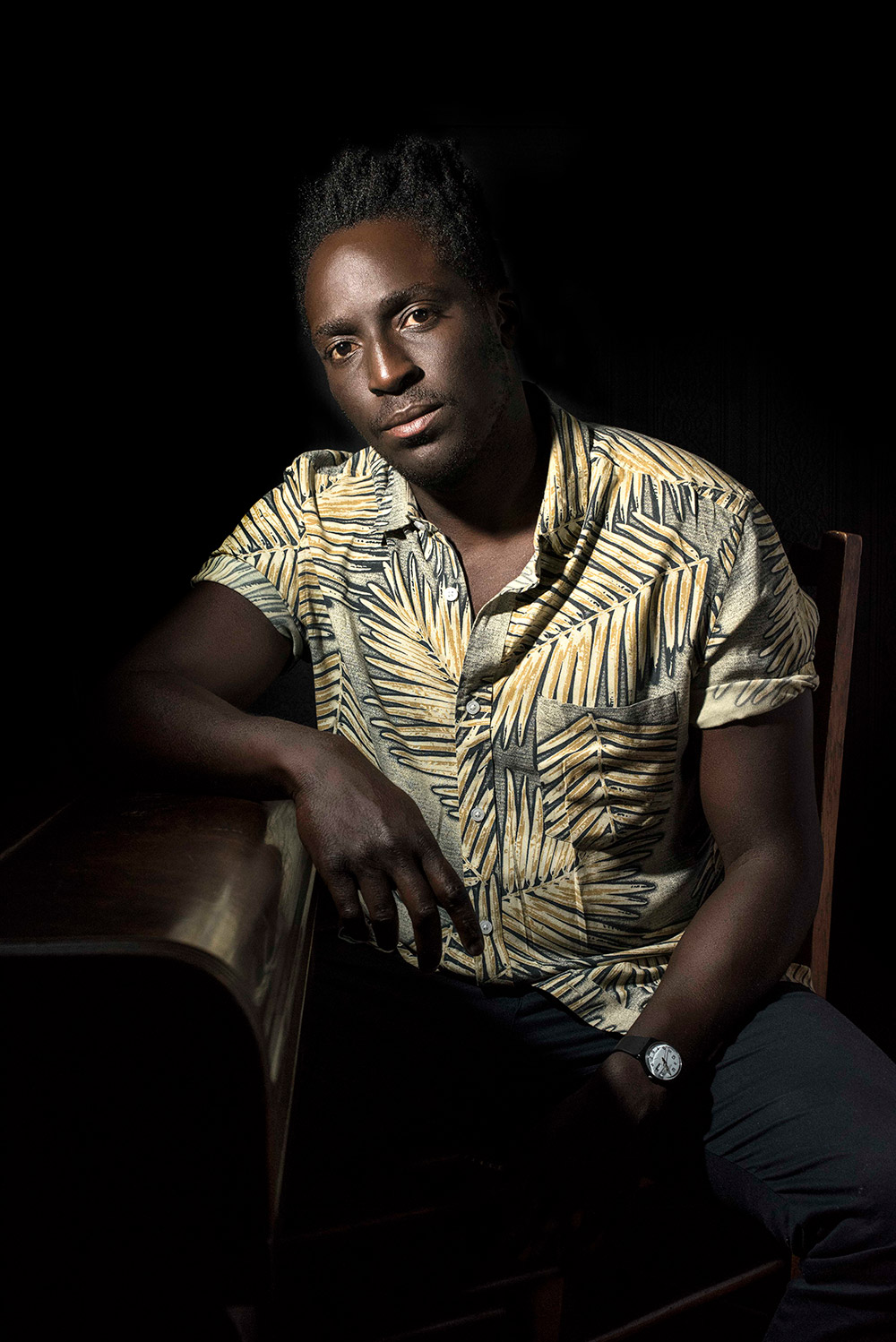

Nikon D810 + 24-70mm ƒ/2.8G | 1/250s ƒ/3.5 ISO 1250 | © Holly Wren

Nikon D810 + 24-70mm ƒ/2.8G | 1/250s ƒ/3.5 ISO 1250 | © Holly Wren

I understand you were privy to the A1 for a long period before the launch. What were your initial thoughts when you finally got to try it?

When they told me there was a new product they wanted me to try, I guessed that it would be a smaller light, an on camera solution; it made sense as Profoto’s range has become more compact and portable in the last few years with the B1X and the B2. Photographers want to bring the quality of their studio lighting kit onto their environmental shoots, and I think that ‘speedight’ market hasn’t been updated for a while, so I was eager to see exactly how they’d interpreted that.

My initial thoughts when I got my hands on the A1 were about how small and portable it is, and the standard of build quality, plus it’s ease of use – picking it up for the first time I was very quickly able to use it without reading a manual.

Here an A1 is held slightly off camera and used to add more light to the scene, but blended seamlessly with natural light | © Holly Wren

Here an A1 is held slightly off camera and used to add more light to the scene, but blended seamlessly with natural light | © Holly Wren

You refer to it as a Speedlight, but Profoto like it to be referred to as a studio flash, why the confusion? Where does this product fit in a photographers lighting kit?

Profoto like it to be referred to as a studio light because it has the features and technical sophistication of their location light be it in a smaller package; but in my opinion the fact that it is the same size and performs on camera like a speedlight, it is largely comparable to one. In fact, I think to not compare it to a speedlight is an injustice to just how well Profoto have done in their improvement on the traditional on-camera flash unit. For a lot of photographers it will replace their speedlight as it corrects some of the frustrations that a more traditional speedlight brings.

I see it as a true hybrid between my larger location lights and my speedlights. In some circumstances it replaces my B2 or B1, but in all circumstances it replaces my speedlight. In fact, I’ve already sold both my Nikon SB910’s, which is a testament to this product.

You can use it as you would a speedlight on camera, as a light off camera, or combine it with other Profoto kit such as the B1X or B2.

You’re a big advocate of the B2’s. How do you think the A1 will fit into your style of shooting, given that the output is lower?

What I’ve discovered using the B2’s is often that I don’t use them on anywhere near full power, often they are set on the lowest power. Primarily that’s because I use them to add an extra bit of clean, beautiful light into an already well lit, natural light led set up. So if I’m using them on the lowest setting, I can substitute them for an A1 easily, without being short of power.

In addition, I sometimes use the B2’s to add a hair or rim light or to light something within a scene, the A1’s are perfect substitutes for this, being small and discreet.

Nikon D810 + 85mm ƒ/1.4G | 1/250s ƒ/3.5 ISO 200 | © Holly Wren

Nikon D810 + 85mm ƒ/1.4G | 1/250s ƒ/3.5 ISO 200 | © Holly Wren

Are there any particular features of the A1 that you feel set it apart from other on-camera systems? Do you ever shoot with Speedlights, and if so, will the A1 replace these for you?

Absolutely. I have used speedlights throughout my career. The A1’s key selling points are clear, and in my opinion means the A1 outperforms its competitors in this on-camera market.

The first is its use of Lithium batteries – meaning you can recharge, see how much battery you have left, and expect consistent power to the end. Farewell to piles of AAs in the bottom of my kit bag and the uncontrollable urge to replace barely depleted batteries with new ones before key shooting moments.

Second is the recycle time, you need to see it to believe it but the A1 literally doesn’t miss a shot. Firing at 12 fps on the D4 you will see no drop off in flash (as long as you’re not at full power on the A1), and anyone shooting events will understand the frustration of getting the shot but it not being lit correctly because the flash cannot keep up with the shooting speeds. That really blew my mind.

Thirdly is it’s much softer and gradual light fall off. I’ve shot portraits with this light on camera, with the flash pointing at my model. Something that I think is a pro- no, no! Profoto are known for their beautiful light, and the A1 delivers this.

Finally, my favourite feature is the ease of use. I honestly could not tell you what half of the menu does on my speedlights. But the A1 cuts the out all the unnecessary and goes straight to the important bits; the large wheel dial lets you easy adjust power or relative power in TTL. And the menu is self explanatory.

Off camera, before I owned the B2’s I used to use a speedlight in a Lastolite softbox (of varying forms) to take portraits which I moved away from because of connection issues, poor recycle times and lack of power consistency. But now the A1’s correct those issues I can go back to using the A1 off camera, instead of the B2s.

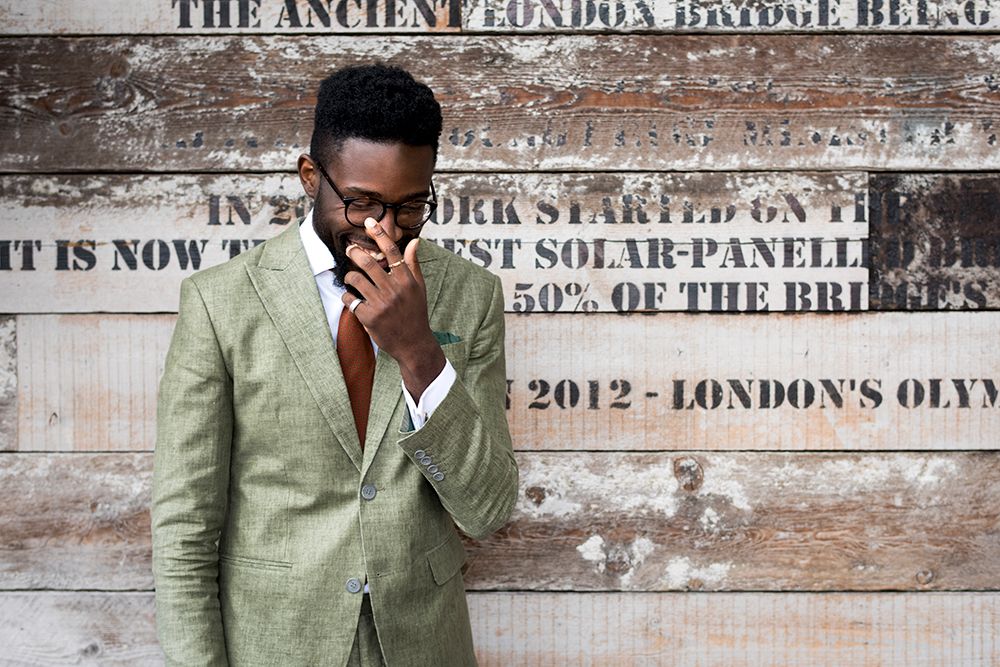

Here the A1 is used on camera as a front fill-in flash. In this shot I exposed for the sky, and the faces are filled-in with the flash, creating a dramatic shot without over exposing the sky | © Holly Wren

Here the A1 is used on camera as a front fill-in flash. In this shot I exposed for the sky, and the faces are filled-in with the flash, creating a dramatic shot without over exposing the sky | © Holly Wren

You demonstrated some interesting setups during the training – some simple and others more intricate. Did you devise these yourself?

Yes. The training was designed alongside the team at Profoto to demonstrate the main features of the product. We wanted to show its strengths, so I designed the set ups to encompass the range of situations that the A1 was capable of performing in, which is why I demonstrated it both indoors and outdoors. I also wanted to show that it could be used on and off camera, as well as for the key light on a portrait or as part of the Profoto system. I think it’s versatility of use is one of it’s key selling points – wedding, portrait, press, event and travel photographers will all have a use for this product for different reasons.

Was the A1 able to deliver the shots you imagined, or did you tailor the setups to accommodate any limitations?

The shots were built to show the A1’s strengths. We didn’t design any of it to show how it would fail!!!! But in terms of it’s limitations, there of course are some. I guess that power is the main one, it’s only a quarter of the power of a B2 so it doesn’t, for example, have capacity to overpower harsh midday sun from a distance, or to replace the flash speed of the D1’s or B1X’s in studio, but that’s not what it’s for. With all photography you have to use the equipment relevant to your needs, will the A1 outperform studio lights? No. But, will it be incredibly useful as an on location flash? Yes.

The best advice I can give, is try it! That’s the beauty of renting before you purchase – try before you buy. Find out if this is the light for you.

Nikon D810 + 50mm ƒ/1.4G | 1/250s ƒ/4.5 ISO 1000 | © Holly Wren

Nikon D810 + 50mm ƒ/1.4G | 1/250s ƒ/4.5 ISO 1000 | © Holly Wren

You seem pretty convinced that the A1’s will form a key part of your kit bag– what’s the catch? How could Profoto improve on them?

The only gripe for me at the moment is the modifiers you can use with the A1. Profoto have launched a range of magnetic ones that you can use to soften the light but for me it needs to go further. I want to see grids and soft boxes that can be used with this system. Which would allow me to go further with their use off camera.

Manfrotto do a handy little gadget called the ‘Snap Tilthead’ which allows you to use them on a lighting stand with an umbrella. I’ve used that set up on a few occasions and it goes that extra way to soften the light but I want to be able to do more!

It would also be nice to see them sold as a pair, I think that most people purchasing these will want two, or at least one with a TTL Air remote so they can be used off camera without buying the remote separately.

An A1, modified with a dome diffuser is used on camera and fired directly at the model | © Holly Wren

An A1, modified with a dome diffuser is used on camera and fired directly at the model | © Holly Wren

Finally, there is a lot of talk about the price, this is not cheap at £849, do you think it’s worth the extra investment?

Well firstly, when was buying any Profoto gear ever cheap? But in the same way you might choose to buy a BMW over a Skoda, you need to consider what you’re getting for the money, and whether that investment is worth it. If you want to travel from A to B, both cars will get you there, but it’s more the experience of the ride that changes. If you care about heated seats, better build quality and a quieter ride you might prefer to drive the BMW. If those things are irrelevant to you, you’d save the cash and buy the Skoda. Either is the right decision, it comes down to what’s important to you, your purpose of use and budget.

The A1 allows me to work quickly, more efficiently and more professionally. It solves the issues I have with speedlights and provides me with the quality of a studio light in a portable package. I can use it on location for portraits as well as on camera at events.

Those factors for me, make it worth the extra spend, but of course, people will decide how much those features are worth to them, and how much of a role the A1 will play in their kit bag.

Holly was talking to Tim Stavrinou.

For more information on the Profoto A1, contact our sales department, or to try before you buy, visit Wex rental